DNA Damage Response and Cancer

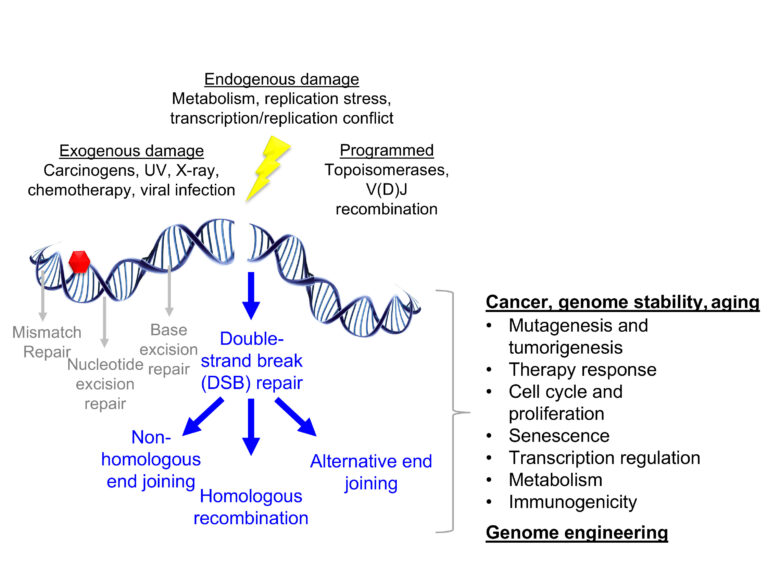

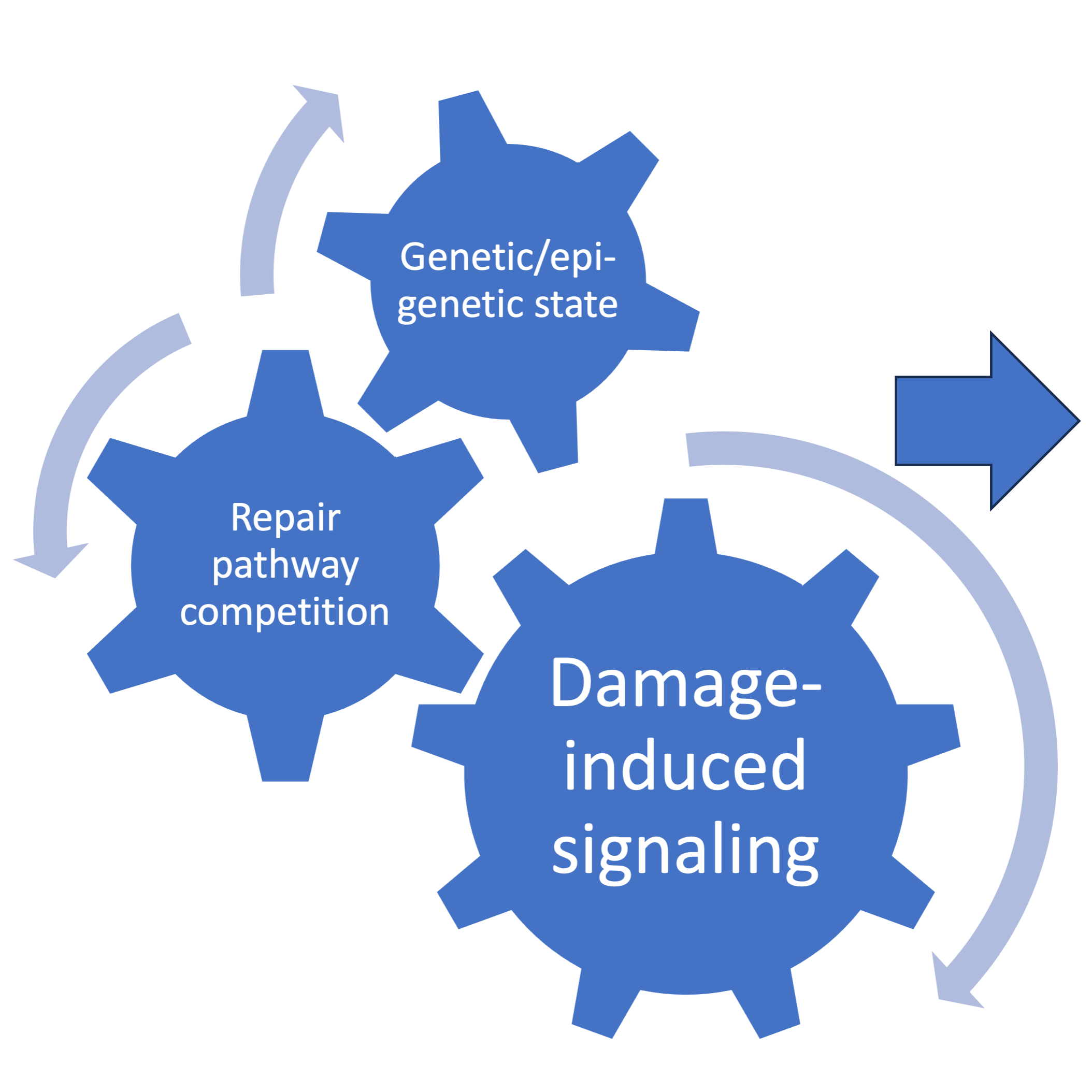

DNA damage arises from a multitude of exogenous and endogenous sources. Double-strand breaks in DNA (DSBs) are one of the most consequential forms of DNA damage for the maintenance of genome stability. Several pathways are available to cells for the repair of DSBs, each of which utilize specific substrates and leave unique genomic scars. As a result, repair pathway selection has wide-ranging consequences for cell and organismal biology, illustrated above. Our lab is interested in how the signaling of DSBs dictates pathway selection and how alterations to these mechanisms can be utilized for therapeutic purposes. Our current projects address the following questions about the connection between damage-induced ubiquitin signaling, genetic and epigenetic states, and the competition between repair pathways:

1) how DNA damage signaling processes are regulated

2) how they impact tumorigenesis and therapy response, and

3) how can they be exploited as drug targets in different genetic backgrounds

Strategies and Techniques

We employ a variety of methodologies to study the DNA damage response including microscopy, next-generation sequencing, cell and mouse genome engineering, patient-derived xenografts (PDX) and cancer models, etc.

Confocal microscopy is a staple of our research. Adaptive deconvolution achieves near super-resolution with fixed immunofluorescence and live-cell imaging techniques.

DNA damage impacts many aspects of cell biology including replication and the cell cycle. We monitor these effects using flow cytometry, immunoblotting, and microscopy. Above is time lapse microscopy of tagged histone proteins in a cell undergoing mitosis during a DNA damaging treatment.

DNA damage response proteins accumulate into foci at sites of damage. These recruitments can serve as pathway biomarkers and can impact cell viability, proliferation, and drug response. Above, DNA (blue), S/G2-phase cells (green), G1-phase cells (red), and gamma-H2AX foci (magenta). Below is an example of how these assays can lead to interesting discoveries:

We develop image analysis strategies to maximize throughput and minimize bias. The example above uses a customized ImageJ macro to identify and quantify DNA repair protein foci at damage sites and evaluate colocalization with other repair factors or cell cycle markers.

Single molecule analysis of DNA fibers provides insights into the biology at replication forks. See the publication below for more details on this fiber assay:

Next-generation sequencing combined with molecular biology techniques can produce unique datasets for the study of DNA damage response studies. The heatmaps above produced from END-seq data provide information about the extent of end resection in each sample.

Transgenic mouse models enable the study of specific mutation impacts on genome stability, development, and disease progression. Learn more about the mice above in our publication:

Patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models, , or tumor tissues extracted from patients and propagated in immunodeficient mice, allow for novel and clinically relevant studies of drug response and resistance. Learn more in our recent preprint (image credit: Kas Nesic):

Constructing tissue microarrays from patient samples or series of PDX models has allowed for semi high-throughput analyses when combined with our image analysis approaches to assess protein biomarkers in clinical samples (image credit: Erica Huelsmann).

Publications

Follow this link for an up-to-date publication list:

Krais JJ#, Glass D, Chudoba I, Feng W, Simpson D, Patel P, Wang Y, Liu Z, Neumann-Domer R, Betsch R, Bernhardy AJ, Bradbury A, Conger J, Nacson J, Pomerantz R, Gupta G, Testa J, Johnson N#. Genetic separation of Brca1 functions reveal mutation-dependent Polymerase Theta vulnerabilities. Nature Communications. 2023 Nov 24;14(1):7714. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-43446-1. PubMed PMID: 38001070; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC10673838. #Co-corresponding author

Nesic K#, Krais JJ#, Vandenberg CJ, Wang Y, Patel P, Kwan T, Lieschke E, Ho GY, Barker HE, Bedo J, Casadei S, Farrell A, Radke M, Shield-Artin K, Penington JS, Geissler F, Zhang F, Dobrovic A, Olesen I, Kristeleit R, Oza A, Ratnayake G, Traficante N; Australian Ovarian Cancer Study; DeFazio A, Bowtell DDL, Harding TC, Lin K, Swisher EM, Kondrashova O, Scott CL, Johnson N, Wakefield MJ. BRCA1 secondary splice-site mutations drive exon-skipping and PARP inhibitor resistance. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2023 Mar 21. PubMed PMID: 36993400. #Equal contribution

Krais JJ, Wang Y, Patel P, Basu J, Bernhardy AJ, Johnson N. RNF168-mediated localization of BARD1 recruits the BRCA1-PALB2 complex to DNA damage. Nature Communications. 2021 Aug 18;12(1):5016. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-25346-4. PubMed PMID: 34408138.

Di Marcantonio D, Martinez E, Kanefsky JS, Huhn JM, Gabbasov R, Gupta A, Krais JJ, Peri S, Tan Y, Skorski T, Dorrance A, Garzon R, Goldman AR, Tang HY, Johnson N, Sykes SM. ATF3 coordinates serine and nucleotide metabolism to drive cell cycle progression in acute myeloid leukemia. Mol Cell . 2021 Jul 1;81(13):2752-2764.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.05.008. Epub 2021 Jun 2. PubMed PMID: 34081901.

Cong K, Peng M, Kousholt AN, Lee WTC, Lee S, Nayak S, Krais JJ, VanderVere-Carozza PS, Pawelczak KS, Calvo J, Panzarino NJ, Jonkers J, Johnson N, Turchi JJ, Rothenberg E, Cantor SB. Replication gaps are a key determinant of PARP inhibitor synthetic lethality with BRCA deficiency. Mol Cell . 2021 Jun 26;. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.06.011. Epub PubMed PMID: 34216544.

Panzarino NJ, Krais JJ, Cong K, Peng M, Mosqueda M, Nayak SU, Bond SM, Calvo JA, Doshi MB, Bere M, Ou J, Deng B, Zhu LJ, Johnson N, Cantor SB. Replication Gaps Underlie BRCA-deficiency and Therapy Response. Cancer Res. 2020 Nov 12;. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-1602. PubMed PMID: 33184108.

Krais JJ, Johnson N. BRCA1 Mutations in Cancer: Coordinating Deficiencies in Homologous Recombination with Tumorigenesis. Cancer Res . 2020 Nov 1;80(21):4601-4609. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-1830. Epub 2020 Aug 3. Review. PubMed PMID: 32747362.

Krais JJ, Johnson N. Brca1 mutations in the coiled-coil domain impede Rad51 loading on DNA and mouse development. Mol Cell Oncol . 2020;7(5):1786345. doi: 10.1080/23723556.2020.1786345. eCollection 2020. PubMed PMID: 32944641.

Krais JJ, Wang Y, Bernhardy AJ, Clausen E, Miller JA, Cai KQ, Scott CL, Johnson N. RNF168-Mediated Ubiquitin Signaling Inhibits the Viability of BRCA1-Null Cancers. Cancer Res . 2020 Jul 1;80(13):2848-2860. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-3033. Epub 2020 Mar 25. PubMed PMID: 32213544; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7335334.

Krais JJ, Johnson N. Ectopic RNF168 expression promotes break-induced replication-like DNA synthesis at stalled replication forks. Nucleic Acids Res . 2020 May 7;48(8):4298-4308. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa154. PubMed PMID: 32182354.

Wang Y, Bernhardy AJ, Nacson J, Krais JJ, Tan YF, Nicolas E, Radke MR, Handorf E, Llop-Guevara A, Balmaña J, Swisher EM, Serra V, Peri S, Johnson N. BRCA1 intronic Alu elements drive gene rearrangements and PARP inhibitor resistance. Nat Commun. 2019 Dec 11;10(1):5661. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13530-6. PubMed PMID: 31827092.

Gabbasov R, Benrubi ID, O’Brien SW, Krais JJ, Johnson N, Litwin S, Connolly DC. Targeted blockade of HSP90 impairs DNA-damage response proteins and increases the sensitivity of ovarian carcinoma cells to PARP inhibition. Cancer Biol Ther . 2019;20(7):1035-1045. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2019.1595279. Epub 2019 Mar 30. PubMed PMID: 30929564.

Nacson J, Krais JJ, Bernhardy AJ, Clausen E, Feng W, Wang Y, Nicolas E, Cai KQ, Tricarico R, Hua X, DiMarcantonio D, Martinez E, Zong D, Handorf EA, Bellacosa A, Testa JR, Nussenzweig A, Gupta GP, Sykes SM, Johnson N. BRCA1 Mutation-Specific Responses to 53BP1 Loss-Induced Homologous Recombination and PARP Inhibitor Resistance. Cell Rep . 2018 Oct 30;25(5):1384. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.10.009. PubMed PMID: 30380426.

Kondrashova O, Topp M, Nesic K, Lieschke E, Ho GY, Harrell MI, Zapparoli GV, Hadley A, Holian R, Boehm E, Heong V, Sanij E, Pearson RB, Krais JJ, Johnson N, McNally O, Ananda S, Alsop K, Hutt KJ, Kaufmann SH, Lin KK, Harding TC, Traficante N, deFazio A, McNeish IA, Bowtell DD, Swisher EM, Dobrovic A, Wakefield MJ, Scott CL. Methylation of all BRCA1 copies predicts response to the PARP inhibitor rucaparib in ovarian carcinoma. Nat Commun . 2018 Sep 28;9(1):3970. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05564-z. PubMed PMID: 30266954.

Krais JJ, Virani N, McKernan PH, Nguyen Q, Fung KM, Sikavitsas VI, Kurkjian C, Harrison RG. Antitumor Synergism and Enhanced Survival with a Tumor Vasculature-Targeted Enzyme Prodrug System, Rapamycin, and Cyclophosphamide. Mol Cancer Ther . 2017 Sep;16(9):1855-1865. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-16-0263. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28522586.

Wang Y, Krais JJ, Bernhardy AJ, Nicolas E, Cai KQ, Harrell MI, Kim HH, George E, Swisher EM, Simpkins F, Johnson N. RING domain-deficient BRCA1 promotes PARP inhibitor and platinum resistance. J Clin Invest. 2016 Aug 1;126(8):3145-57. doi: 10.1172/JCI87033. Epub 2016 Jul 25. PubMed PMID: 27454289.

Wang Y, Bernhardy AJ, Cruz C, Krais JJ, Nacson J, Nicolas E, Peri S, van der Gulden H, van der Heijden I, O’Brien SW, Zhang Y, Harrell MI, Johnson SF, Candido Dos Reis FJ, Pharoah PD, Karlan B, Gourley C, Lambrechts D, Chenevix-Trench G, Olsson H, Benitez JJ, Greene MH, Gore M, Nussbaum R, Sadetzki S, Gayther SA, Kjaer SK, D’Andrea AD, Shapiro GI, Wiest DL, Connolly DC, Daly MB, Swisher EM, Bouwman P, Jonkers J, Balmaña J, Serra V, Johnson N. The BRCA1-Δ11q Alternative Splice Isoform Bypasses Germline Mutations and Promotes Therapeutic Resistance to PARP Inhibition and Cisplatin. Cancer Res . 2016 May 1;76(9):2778-90. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0186. PubMed PMID: 27197267.

Heinzelman P, Krais JJ, Ruben E, Pantazes R. Engineering pH responsive fibronectin domains for biomedical applications. J Biol Eng. 2015;9:6. doi: 10.1186/s13036-015-0004-1. eCollection 2015. PubMed PMID: 26106447.

Krais JJ, De Crescenzo O, Harrison RG. Purine nucleoside phosphorylase targeted by annexin v to breast cancer vasculature for enzyme prodrug therapy. PLoS One . 2013; 8(10): e76403. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone. 0076403. eCollection 2013. PubMed PMID: 24098491.

Van Rite BD, Krais JJ, Cherry M, Sikavitsas VI, Kurkjian C, Harrison RG. Antitumor activity of an enzyme prodrug therapy targeted to the breast tumor vasculature. Cancer Invest. 2013 Oct;31(8):505-10. doi: 10.3109/07357907. 2013.840383. PubMed PMID: 24083814.

Neves LF, Krais JJ, Van Rite BD, Ramesh R, Resasco DE, Harrison RG. Targeting single-walled carbon nanotubes for the treatment of breast cancer using photothermal therapy. Nanotechnology . 2013 Sep 20;24(37):375104. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/24/37/375104. Epub 2013 Aug 23. PubMed PMID: 23975064.